You’ve decided to invest in companies and you’re buying stocks. Congratulations. How do you measure stock performance?

This is a really tough question. Deciding to make the leap from mutual funds and ETFs to directly investing in companies is a big decision. It’s a decision to rely on your abilities over an index or fund manager.

What Advantage Do We Have Over the Pros?

Why would we do this? Professional fund managers have years of experience. They typically have investment and analysis teams that provide them with crucial information about markets, economies, and companies around the globe. They often have MBAs from prestigious universities. How can I compete with that?

The advantage you have is time.

This will sound familiar to those who read the post on compounding. Let’s talk about why.

Fund Management is Tough

Let’s take a look first from the perspective of an investor shopping for a mutual fund. The first thing we look at is the fund’s performance. We want to buy a fund that has a solid track record of outperforming over a 1 year, 3 year, 5 year and 10 year period. Why would we buy a fund that underperforms. That’s crazy-talk.

So, flip this around to the fund manager’s perspective, and the fund company’s perspective. Their funds need to beat the market over these periods or else no one will buy them. The salaries and bonuses of the investment professionals in these firms are tightly coupled with fund out-performance.

These investment professionals often can’t afford to hold onto a losing stock for too long even though they may know in their hearts it is a long-term winner.

Here’s Our Advantage

You and I are not held to these same standards. We don’t have investors who are pressuring us to beat the market every quarter as well as in the 1,3,5 and 10 year periods. For us, we just want to ensure we have a solid retirement nest egg or are able to help send our kids to college.

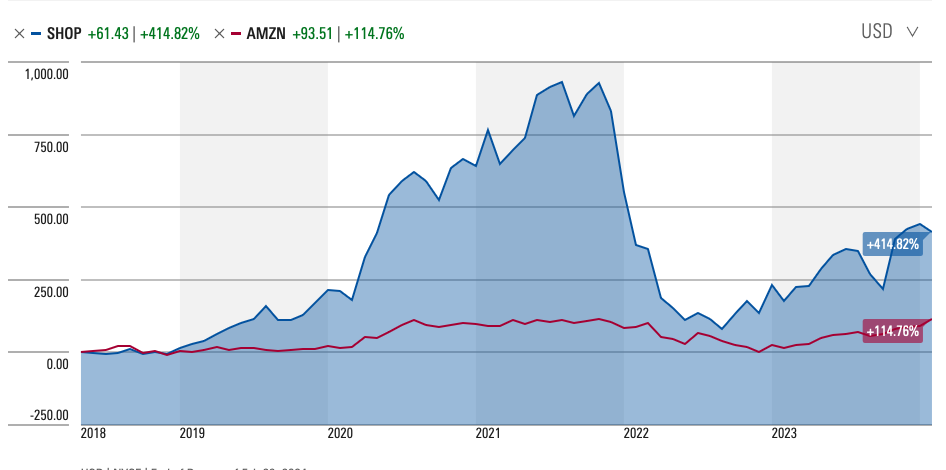

In the post on The Secret to Building Wealth, I talked about my experience with Shopify. This was a company I invested in and watched it go up/down/up/down over and over for about a year. If I were a mutual fund manager, I would be explaining to my boss and my shareholders each quarter why I was continuing to invest in this dog when the stock price of Amazon, the proven leader in this space continued to go up. The pressure to sell would have been huge.

Today, after lots of angst over the fluctuations that Shopify went through, I’m sitting on a 420% gain. The $5,000 I invested in May of 2018 is worth over $26,000.

Amazon was up 115% during that time period. Not too shabby,

Here’s a chart that shows Shopify’s stock price change since May 2018 v Amazon

Stick to Our Convictions

We often hear the phrase that “I am my harshest critic”. This rings true for many of us. If that is the case, then in the example above, while we don’t have bosses and shareholders judging our performance, we are judging it ourselves, and quite harshly I might add.

With my Shopify experience, there were times where I felt like an idiot. And the Shopify experience was similar to my experience as an investor in Netflix, Amazon and Apple. Remember the Netflix Quickster debacle. Click here if you missed it. That sent many an investor running for the door. For those who stayed, it took a long long time for the stock price to recover.

I want to be clear. Our advantage isn’t that we can buy any stock and hold it through the down-turns and win in the end. Our advantage is that if we do our research well and identify a company that has a huge opportunity and has demonstrated an ability to win market share, we can stick to our convictions and ride out the volatility. We won’t always win. For every Shopify in my portfolio, there are 3 or 4 that went the other way. In some cases, I stuck to my convictions and rode them to the bottom (Yellow Trucking) and some I bailed on before they hit zero. See my post on when to sell.

Time is our advantage

How to Identify Great Companies

If I really knew how to do this, I wouldn’t be sitting in the cold in New England writing a blog post, I’d be lounging on the Riviera. But looking back at my successes and failures, I see some patterns.

Going back to the post on Stocks, I recommended books by Peter Lynch. In one of his books he talked about how he noticed the L’eggs eggs all over his house. His wife and daughters seemed to buy an awful lot of them. Lynch talks about how it caught his attention and then the research process he went through to decide if this was an investment opportunity. You’ll have to read One Up On Wall Street if you want to know how the story ends.

The wild idea or observation is the catalyst. The research that follows is what builds conviction. Just because there are lots of eggs around the house doesn’t mean this is a good business. What company produces them? Who runs the company? How much do they sell? What’s the addressable market for the product – what % do they have now, what % do they expect to have and what’s the path to get there? Who is their competition? Is the company profitable?

The idea kicks off lots of analysis. If this sounds like fun to you, great, you’re reading the right post. If not, that’s OK, it is not fun for many. These folks have more interesting hobbies. For those folks, read the post on Mutual Funds.

If it sounds like fun, do the research and create your thesis. Document for yourself your reasons for buying, or for not buying, shares in this company. This process is what builds conviction. Click here to learn more about creating a thesis.

Test Often, But Don’t React

The companies of which you hold shares will report earnings on a regular basis. Most report quarterly. Each report is an opportunity for you to test your thesis against the companies actual performance. If the company projected 20% growth in customers annually, are they on track? If they expected to become profitable this quarter, did they?

What are management’s expectations for the coming quarter and the coming year? Are they consistent or has something changed?

The earnings release gives us lots of data to compare against our thesis and see if our convictions still stand. If the company missed on a thesis point or 2, it may give us some pause, but we have the ability to stay the course. Keep going another quarter or 2 or 3 or 4, depending on how strong your conviction is, and see how things play out.

I wrote a post on stocks and when to sell, so I wont’ rehash that here.

Another Example: Amazon

I bought my first shares of Amazon in the early 2000s. I sold some but then bought back in and held on in 2010. Those shares are up 2,404%. I had a thesis for Amazon that was based less on financials and more on the growth story. If you looked closely at Amazon and you read Jeff Bezos’ shareholder letters, you could see the growth story play out. The story would drive the stock price up, and then earnings would come out and the profits investors were hoping for wouldn’t be there. Management was investing all available cash into the business instead of making a profit. Again and again this happened. One quarter it would turn a profit and investors would celebrate that Amazon had finally turned the corner. Next quarter, a loss.

Most quarters, the stock price dropped 10-20% after earnings. I used the opportunity to pick up a few more shares. My thesis hadn’t changed. I still had a strong conviction.

Why Did I Believe I Was Right?

I initially got interested in Amazon because it was a fantastic way to buy books. It was a bookstore, then it was an everything store, then, out of nowhere Amazon Web Services (AWS) showed up. Then it was a logistics player, first automating its warehouses, and then building out an infrastructure with planes, tractor trailers and delivery vans. Now they are becoming a big player in advertising, which the folks at Google and Facebook will tell us is fairly lucrative.

Looking back now, this seems a no-brainer. Go back to 1997 and bet it all on Amazon. But the road was bumpy. When an established company, like Amazon was in the 2010s, can’t turn a profit and all the experts (guys with MBAs who know a lot more than me) are selling, it’s hard to stick to your convictions.

Sometimes I’m Wrong

I’ve been pretty good at sticking to my convictions and this has rewarded me in many cases. But, for every Amazon, Apple and Netflix, there is an Under Armor.

I loved Under Armor. Similar to Peter Lynch’s story on the L’eggs eggs, my wife and I both noticed how Under Armor was everywhere. It seemed very much like Nike, another of my long-term holdings, was in its early days. I did a little research and bought shares in 2010. I bought a little more at various points through 2015. The rise for that initial purchase was meteoric. It kept going up. People kept wearing it, more and more sports teams were wearing Under Armor products. It looked like another Nike.

I went through some earnings seasons where inventories became a problem. They had too much stuff. They were discounting to get it off the shelves. They spent a lot of money on myfitnesspal, a fitness app, that didn’t seem to be a great use of capital. Then there was trouble in the management ranks. Some high level resignations, and then the founder was looking to split the share classes to give him more control. Over quarters and years, my thesis began to deteriorate, but I held on until 2020 when I decided I could find a better use for the remaining dollars I had in Under Armor shares.

Interestingly, the original shares were still up 80% when I sold them. This helped offset the 28% and 78% declines of the subsequent purchases.

Paying For Your Education

I lost money on Under Armor, but I learned a valuable lesson. To this day I love Under Armor. I have their golf shirts, workout clothes, cold weather gear, and I even used the myfitnesspal app religiously and loved it. It’s possible to be a great company and a bad investment. Also, 5 years is probably a little too long to hold onto a company that is not sticking to your original thesis. I loved the products and I hoped the company would turn around. Hope is not a strategy. Nor should your conviction be based on hope.

You get this lesson free. I had to pay.

Recap

Interesting stories, but what do we do with it all?

First, I would say that the advantage we have over fund managers is real. The fact that we can stick to our convictions without pressure from bosses and shareholders can allow us to realize huge returns from companies with an uneven growth trajectory – like Amazon and Shopify.

Next up, it is important to remember or write down why we invested in the first place. What was our investing thesis? Continue testing that thesis over the lifetime of our ownership, but expect that our thesis will not hold up 100%. As long as you believe that it is largely holding true and you believe in the folks running the company, stick with it for a while.

How long is a while? Good question. More than a quarter or 2, but less than Under Armor – 5 years-ish.

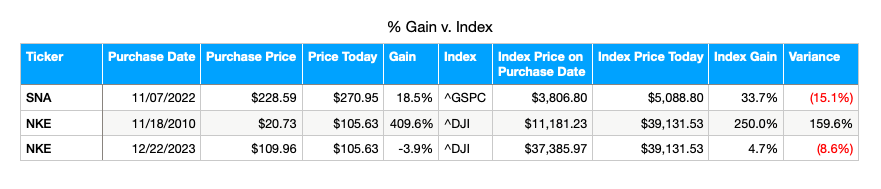

Keep score. While you are evaluating a company’s progress against your thesis, see how the stock price is doing against the various market indices. Is it outperforming over long periods as you had anticipated? If not, you might be better in an index fund or another investment. I have an example below.

Diversify – Don’t put all your eggs in one basket. I like to invest in companies. For me it is a hobby and I’ve done well overall. I also hold 1 year treasury bonds, I-bonds, bond mutual funds, High Yield savings accounts, CDs, and lots of index funds. See my post on asset allocation for details.

Sometimes I beat the index, sometimes I don’t. Buying the index guarantees you’ll match the index (less fees, but pretty close).

Bonds and Cash help me ride out the volatility in stocks.

That’s the recap, let’s talk a bit about keeping score.

How to Keep Score

Brokerage firms do a good job of showing us our holdings, the individual positions and the gain/loss. I also like to keep my own spreadsheet that measures individual purchases against a benchmark. How is my Amazon purchase tracking against the NASDAQ? How is Nike doing against the Dow? How is Snap-On tools doing against the S&P 500?

If you use Excel or Mac-OS Numbers this is easy to do. Create a sheet with ticker symbol, price paid per share and purchase date. Then add the ticker symbol for the index you want to compare (for example ^GSPC for the S&P 500). Both spreadsheets have a Stock function that will return the historical price.

Stock Scorecard Example

A picture is worth a thousand words, so let’s take a look.

The first 3 columns are from my brokerage account. I used the stock function to get today’s price for Snap-on (SNA) and for Nike (NKE). Gain is a calculation – difference between the price today and the purchase price divided by the purchase price. I keyed in the symbol for the index and then used the same stock function to get the price on purchase date and the price today. Variance is the difference between my stocks % gain and the index % gain.

Nike since 2010 is killing the index. Once again, time and the magic of compounding works wonders. Nike also pays a dividend, which I’ve reinvested in more Nike shares so my total return is even more impressive.

Nike in the past few months has been a disappointment. I haven’t made any other purchases, but Nike has been pretty flat over the past few years. Not good for new investors, but still good for long-term holders.

Snap On is lagging the index. Snap On, however, pays a 2.75% annual dividend and Snap On has increased its dividend every year since 1995, making it a dividend aristocrat. While the stock price may lag the index, the dividend may make the total return of this investment a better bet. We’ll talk about measuring this in an upcoming post.

It’s important to look at the individual purchases as well as the overall stock performance. Buying Nike in 2010 allows me to better handle short-term headwinds. I feel better about my convictions as they’ve paid off over 14 years. It helps me deal with the short term loss and be confident it will be a long-term winner as long as the quarterly results don’t provide any negative trends.

As always, let me know your thoughts and questions. More on stocks and keeping score coming soon.

Is Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) a good yardstick to measure performance?

Absolutely. CAGR tells us if our companies are growing, which is why we invest in the first place.