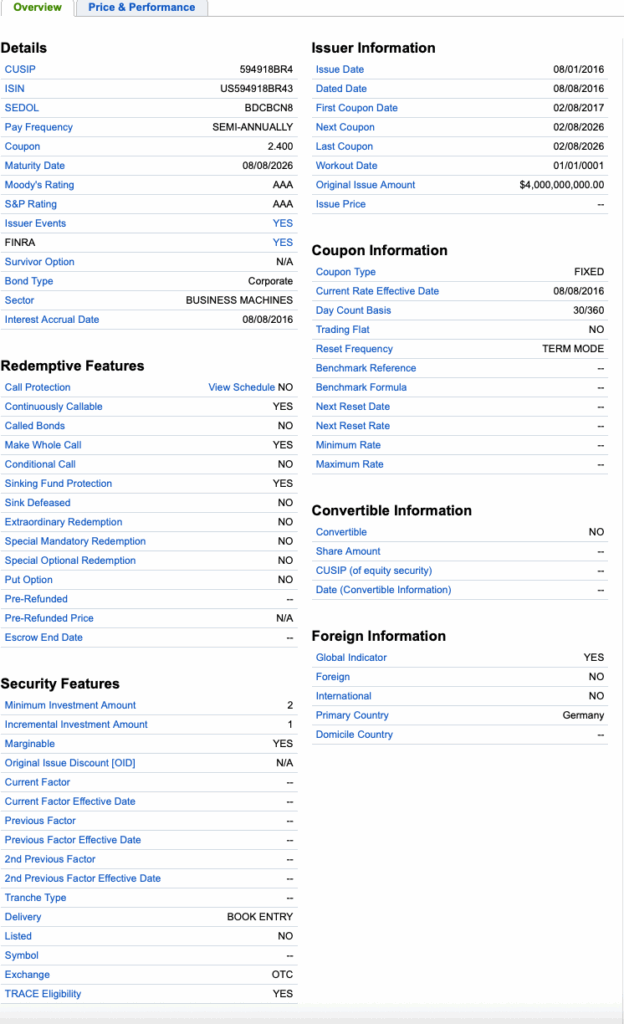

I worked in the investment field for over 30 years but never spent much time with bonds. So to me, bonds are a bit of a mystery. I’m looking to buy a nice simple corporate bond. Check this out.

I understand the maturity date, ratings, coupon and lots of other stuff, but I’ve got no idea about some of the stuff here like the 2nd previous factor effective date.

And even if I understood it all, what’s the benefit. I’m not going to be a bond trader. I’m an investor. I buy and hold. If I buy this bond, the coupon is 2.4%. I’ll get 2.4% in interest until 2/8/2026 and then I’ll get my original investment back.

Of course that’s only true if the company doesn’t go bankrupt. Though this one is Microsoft, so not likely.

Stocks

Compare that to public companies. I can buy shares and there is a potential for windfall capital gains, and sometimes a nice dividend to go along with it.

Neighbor Mike texted me yesterday about his recent 21% run-up in Tesla. As you may recall, I told him in an earlier post the timing wasn’t right for me. Smart move on my part.

Stocks are exciting. There are large swings but a basket of well-researched stocks is likely to treat us well. The S&P 500 has averaged over 10% gains per year with dividends reinvested over the last 100 years or so. That’s a lot of cheese.

Where’s the Love?

However, bonds still deserve some love.

For me, I reserve my love for bond funds. The only exception I make is US treasuries. You can read more about treasuries here.

Bond funds have an important place in our portfolio. It’s important to understand why and how they work. Let’s dive in.

Why Bonds?

2 reasons. Volatility and income.

Volatility

The market can be crazy. The S&P 500 has tanked a jaw-dropping 6 percent in a day. That’s scary.

The S&P 500 has been down 30% or more several times. That’s scary too.

Having some of our assets in bonds can help us navigate the crazy market swings.

Also, if we have money we plan to spend in the next 5 years, we don’t want to risk that in the equity markets. A pull-back could leave us short. Bonds are a good place to lessen risk while getting some income.

Income

Retired folks like me don’t get a paycheck. But oddly, I still need to pay my bills. Doesn’t seem right.

But until this changes, I need to make my own income.

Bond funds are a great way to do this.

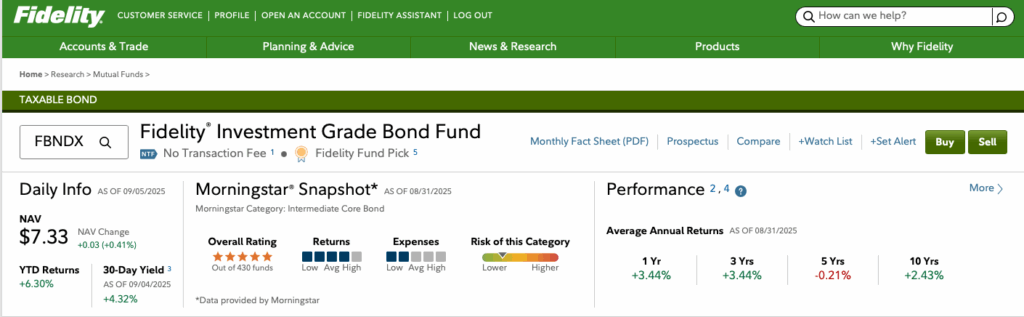

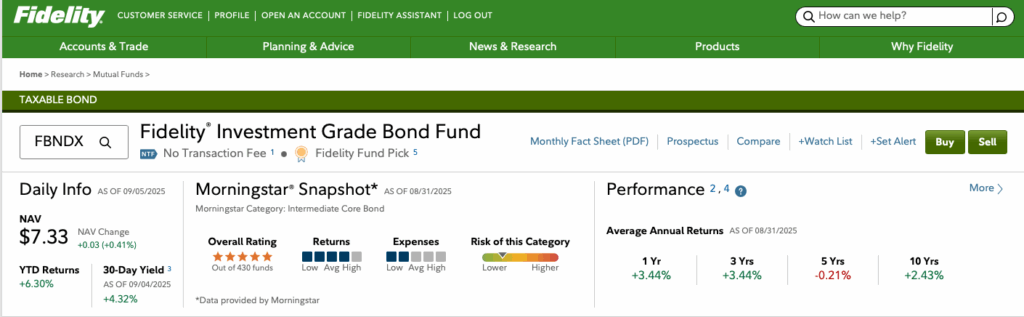

I can choose a nice Investment Grade Bond Fund and enjoy a 4.32% yield.

That means that if I put $10,000 in this fund, I’ll get roughly $432 per year in interest. We’ll talk more about this because it is a little more complicated than that.

But the point is, a bond fund is a nice way to generate some income.

What are Bond Funds?

We’ll start with bonds. When we buy a bond, we are essentially loaning money to the bond issuer.

In the example above, Microsoft is the bond issuer. It needs a quick $4 billion, probably to fund its AI work. Selling bonds is one way Microsoft can quickly get a huge sum of money.

Note, even though Microsoft is looking for $4 billion, the individual bonds will be sold to many investors at $1,000 face value (par value) each.

If I buy this Microsoft bond, I am giving Microsoft some cash. Microsoft will pay me 2.4% per year until maturity, and then Microsoft will return my original bond purchase amount in full.

Now, bonds are complicated, so for me, I like a nice bond fund or ETF. This is a basket of bonds chosen by a fund manager, or by a computer model in a passively managed index bond fund.

The fund or ETF decides to buy and sell bonds in order to meet the fund’s objective. Usually this is some combination of interest income along with capital gains.

A fund will tell you its objective in its prospective or on its home page.

Types of Bond Funds

There are many types, but we’ll stick to 3 today.

Investment Grade

Companies like Moodys and Standard and Poor rate bond issuers. This is an important role. In the case of Microsoft, they’ll look at the company’s debt, assets, cash on hand, and other factors and determine a rating. Healthy companies like Microsoft get a high score and are considered investment grade – fairly dependable investments. The better the score, the lower interest the company will need to pay on the bond.

Just like us. The credit agencies give us a credit score. If we have a high score, we can borrow money at lower interest rates.

Highly rated companies like Microsoft have a high likelihood that they’ll be able to make their income payments and return our initial investment in full at maturity.

High Yield

Also lovingly known as junk bonds.

These are struggling companies. Struggling companies need loans to keep them afloat and help them become profitable again. They’ve got a low rating from the agencies, and just like us when we have a low credit score, they’re having to pay higher interest rates.

As an investor, if we buy a bond in a struggling company, we’ll get a higher income payment, but we’ll take the risk that the company could default and stop making interest payments, or go bankrupt and not be able to return our original investment.

We need to balance the reward of higher interest payments with the risk of losing money.

Municipal Bonds

Municipal bonds, or Munis, can be investment grade or high yield. Munis are issued by federal and state government agencies and generally receive some tax benefits.

If I buy a Federal municipal bond or fund, I will not pay federal tax on the interest. If I buy a state bond or fund for the state in which I live, I will not pay state tax either.

There are exceptions. Some munis are taxable. Check closely.

Duration

Bond fund objectives specify the durations of their bonds.

In general, a short duration bond is less risky than a long duration bond.

Let’s look at an example of why long duration bonds can be risky.

If I buy a 20 year treasury, I get a fixed rate of interest and I get my full purchase price back at maturity. Simple.

But what happens if I need to sell my bond before maturity? I need to sell at market prices. And while bonds are typically less volatile than stocks, they can be volatile at times.

Example

If I bought a 20 year treasury for $1,000 that paid 1% interest and I need to sell it when rates have jumped to 5%, no one is going to give me $1,000 for mine when they can get a shiny new one from the US treasury that pays them 4% more.

In order for me to sell mine, I have to reduce the price to match the total return of the new treasuries. This is fairly simple math.

My bond pays 1% or $10 per year on my $1,000 purchase. Over 20 years, I’ll receive $200 in interest.

The new bond pays 5%, so $50 per year or $1,000 in interest over 20 years.

The difference between the 2 is $800 over the 20 year life of the bond.

That means that I need to reduce my bond’s price by $800 to $200 to provide the buyer with the same total return as the new bond. I take an 80% loss.

Who said bonds aren’t volatile?

And as you can see, a 1 year treasury bond carries much less risk. Even if interest rates spike, I only need to drop my price by enough to cover 1 year of interest differential. So my $1,000 1 year bond would only drop to $940 or 6%.

Choosing

So how do I choose?

First of all, tax free munis are a great choice for a taxable brokerage account. We trade a slightly lower return (than a comparable corporate bond) for a tax benefit. Tax free interest is nice.

Tax free munis are not a good choice in a traditional or Roth IRA or 401k. In these accounts, we’ll pay taxes on all amounts when we withdraw, because the whole account is tax-advantaged. So there is no benefit to holding lower-income munis in these accounts.

Capital Gains

For bonds, we typically focus on the income. One fund has a 4% yield, that’s better than a 3% yield.

Maybe, maybe not.

Our bond fund is trading bonds to meet its objectives. When it sells a bond, it may sell it at a higher or lower price than the fund paid initially. The difference is the capital gain or loss.

If the fund bought a 5 year Microsoft bond for $1,000, got the 2.4% interest for a year, and then sold it for $1,010. The fund made a $10 or a 1% gain on this sale.

Funds trade bonds every day trying to balance capital gains and income to meet its stated objective.

Bond funds publish their YTD Return which shows us the capital gain and the income today.

FBNDX yields 4.32% in a year. We’re only 8 months into 2025, so the fund has only gotten 8/12 of the 4.32%. How does it have a YTD return of 6.3%?

Capital gains.

The price of FBNDX was $7.08 on January 2, 2025, but it’s risen to $7.33 today. And remember, the price is derived by taking all of the assets of the fund and dividing by the number of shares owned. The fund’s assets have risen because the value of those assets have increased. That’s a capital gain.

Realized v. Unrealized

In the example above, we had a realized gain because the fund sold its Microsoft bond. A sale creates a realized gain or loss. When a fund takes a realized gain or loss, it keeps records and at the end of the year will pay out any net realized gains to shareholders. You may have seen this on your statement and wondered what it was. Now you know.

Unrealized gains and losses come from price changes. Funds need to value their assets on a daily basis. For many securities this is easy. If they trade on an exchange, they can just look up the closing price.

So if we held and didn’t sell the Microsoft bond, we’d still see that it had increased in value and the $10 increase would be added to the fund’s value, increasing the fund’s share price.

You can read the details about how mutual funds work here.

Choosing

Now that we understand that we earn from both yield and capital gain, let’s think about how we choose.

First we need to determine our objective.

I am retired and need some steady income, so I have a large chunk of my bond fund investment in an ultra short term conservative bond fund. This invests in short duration treasuries and other safe securities. Of course, since it’s low-risk, the interest is relatively low.

So, to offset the lower interest, I put a little of my bond allocation in high yield (junk) bond funds. I’ll get an extra few percentage points in interest. One of them gets 12.63% per year.

But, because these are bonds issued by distressed companies, I know some of the companies will default. But I also know some won’t. I let a fund manager worry about that.

While this particular fund has paid me 12.63%, the price is down almost 9%. Some of this could be market concerns, but its mostly from bonds that are now worth less than their purchase price (as the issuing companies have struggled).

This is complicated.

Buy a basket of bonds through a fund or ETF and let the professionals deal with it.

Yields Change

And just to make it more complicated, the yields change. Just because a fund pays 4% today, doesn’t mean we’ll get 4% tomorrow. When interest rates go down, the bond’s yield will drop. Maybe not right away, but as it trades bonds it will start buying new bonds with lower interest rates which will bring down the yield of the fund.

So keep your eyes open. The yield will vary with the bond market yields.

If this isn’t cool for you, you may be better off in a long-term CD, whose rate won’t change.

Wrap Up

Bond funds are a great way to earn income.

The 2 funds we talked about are at opposite ends of the spectrum, but there are all types of bond funds in between. All have different objectives, yields and total returns (including capital gains and loss).

The beauty of funds is that we can buy in small amounts so we can buy a basket.

I own 17 bond funds.

The bulk of my bond fund money is in conservative funds, but I supplement with some high yield funds and some longer duration corporate bonds to generate some extra return.