I’ve been thinking a lot about my post on taking social security at 62. You can read the post here.

To give you the Reader’s Digest version, I performed some analysis and determined that I’d likely be better off taking a lower social security payment at 62 and investing all of it in a low-cost S&P 500 fund for 8 years rather than waiting until 70 to start my payments.

The strategy is to take the smaller payment now, invest all of it, let it grow, and then use the gains to supplement my payments starting at age 70.

Will it Work?

I would never advise someone to put money they need in the next 1,2,3,4,5 years into equities. Even a diversified equity investment like an S&P 500 fund can lose money over shorter periods of time.

However, holding for longer periods almost always helps us ride out the short term volatility.

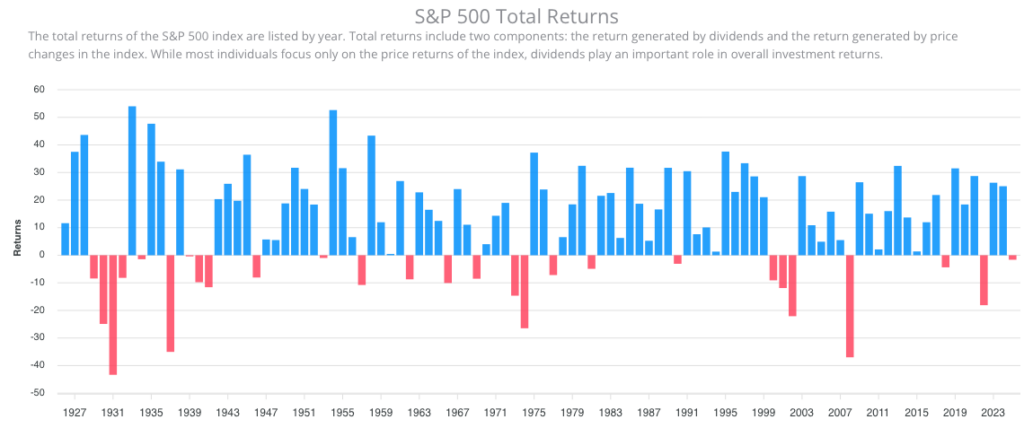

Here’s what a chart of the annual returns of the S&P 500 looks like. You can find it here.

If we eyeball, it’s clear that the S&P 500 goes up more than it goes down and looking at most 8 year periods, it has a pretty good run. We also know that over the past 100 years or so, the S&P 500 has averaged 10% annual returns with dividends reinvested.

Looks like a solid plan.

Are You Sure?

I like education. I like writing and teaching about how things work so that people can make informed decisions. I’ve never wanted to be a financial advisor or to give advice in any way, because I would hate for that advice not to work out. I’m pretty conservative when it comes to money, but still, the market can be irrational longer than we can stay solvent.

So I’m feeling a little like I’ve given advice on when to take social security. So, I’m thinking about whether this is good advice or not. And since it relies on the market and there are no guarantees, I’m comfortable making the decision for myself, but a little uneasy sharing the strategy.

Homework

Worrying won’t get me anywhere, so let’s roll up our sleeves.

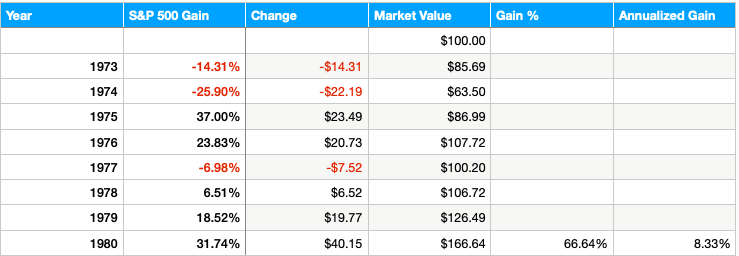

First I looked at a rough 8 year period to see how we’d do. I started with 1973 – 1980.

1st column is year. 2nd column is the annual total return from the chart above. Total return means the dividends were reinvested. In the market value column, I start with $100. In 1973, I apply the -14.31% return and update my market value. I do this for the next 7 years.

I end 8 years with a 66% gain, which is about 8.3% annual return. Not bad for a rough start.

How Can I Check All Periods?

This is a good start, but I really should check 1974 – 1981, 1975 – 1982, 1929 – 1936…and on and on. I’m retired but who has that kind of time.

In order to satisfy myself, I brought on an assistant to help. Luckily the assistant works for free.

Who works for free you ask? AI, that’s who. Meet Grok.

Grok

Grok is the x.ai entry into the AI field. If you read my post on Elon, you know x.ai is a Musk company.

I asked Grok to look into how many 8 year periods would an investor in the S&P 500 have lost money. The answer is likely 2-4 periods. The reason it is likely is that Grok did not have a full dataset and needed to analyze patterns to come up with an answer. It’s pretty fascinating. Check out what Grok had to say.

Response From Grok

To determine how many 8-year periods in the S&P 500’s history have resulted in investors losing money, we need to look at the index’s long-term performance, typically measured by total return (price appreciation plus reinvested dividends). While I don’t have access to a complete dataset to calculate every single 8-year period up to March 24, 2025, I can provide an answer based on historical trends and available data up to the most recent updates, supplemented by general patterns in the S&P 500’s performance.

The S&P 500, launched in its modern form in 1957, has a history of delivering positive returns over longer time frames due to the upward trajectory of the U.S. economy and the compounding effect of dividends. Historically, the average annual total return of the S&P 500 has been around 10% before inflation (and roughly 6-7% after inflation). Over shorter periods, losses are more common—about 1 in 4 years ends in the red—but as the investment horizon lengthens, the likelihood of a negative return decreases significantly.

For 8-year periods specifically, we can analyze “rolling periods” (e.g., 1928-1935, 1929-1936, etc.) using data that extends back to 1928, when the S&P 500’s predecessor indices provide a reasonable proxy. Losses over 8 years are rare because this duration is long enough to smooth out most market downturns, such as bear markets or recessions, which typically last less than 2 years. However, certain exceptional periods of prolonged economic stagnation or severe market crashes could lead to negative returns.

One well-documented period of poor performance is the “Lost Decade” from 2000 to 2009, which spans 10 years and includes the dot-com crash and the 2008 financial crisis. The annualized total return for the S&P 500 from January 2000 to December 2009 was approximately -0.9%, meaning a cumulative loss over that decade. If we examine 8-year subsets within or near this period—such as 2000-2007 or 2001-2008—we find that some of these periods also resulted in losses. For example:

2000-2007: The S&P 500 experienced a modest gain, but when adjusted for inflation, returns were close to flat or slightly negative in real terms.

2001-2008: This period, encompassing the dot-com bust and the start of the financial crisis, saw a cumulative decline in nominal terms, with the index dropping significantly by late 2008.

Another historical period to consider is the Great Depression and its aftermath. From 1929 to 1936 (an 8-year span), the market suffered massive losses due to the 1929 crash and a slow recovery. The S&P 500 (or its equivalent index at the time) lost substantial value, and even with dividends reinvested, the total return was negative in nominal terms for several years, likely extending to an 8-year loss in some rolling periods (e.g., 1929-1936 or 1930-1937).

Looking further, the 1970s stagflation period (high inflation and low growth) also challenged investors. For instance, an 8-year period like 1966-1973 or 1974-1981 might show negative real returns (after inflation), though nominal total returns often remained positive due to dividends. Since your question doesn’t specify whether “lost money” refers to nominal or real returns, I’ll assume nominal total returns unless otherwise implied, as this is the standard interpretation for such queries.

Based on historical analysis:

From 1928 to 2023 (95 years), there are 88 possible 8-year rolling periods (1928-1935 through 2016-2023).

Negative nominal total returns over 8 years are rare and typically tied to major economic disruptions. The most notable periods include:

- 1929-1936: Negative due to the Great Depression.

- 2001-2008: Negative due to the dot-com crash and financial crisis.

- Other periods, like parts of the 1970s, may have been negative in real terms but positive in nominal terms.

Since the S&P 500’s modern inception in 1957 through 2023 (67 years), there are 60 possible 8-year periods (1957-1964 through 2016-2023). The 2001-2008 period stands out as a clear nominal loss. Earlier periods like 1966-1973 might come close but often eked out small positive nominal returns thanks to dividends.

Given the strong bull markets since 2009 (e.g., 2010-2017, 2011-2018, etc.), most 8-year periods after the financial crisis have been positive. Up to March 24, 2025, assuming no dramatic crash in 2024 or early 2025 (which current trends don’t suggest), the count of negative 8-year periods remains low.

Final Estimate: Across the full history from 1928 to 2023, likely 2 to 4 8-year periods resulted in negative nominal total returns, with 1929-1936 and 2001-2008 being the most certain. Since 1957, 1 to 2 periods (notably 2001-2008) are likely candidates. The exact number depends on precise start and end dates for each rolling period, but losses over 8 years are historically uncommon due to the market’s long-term upward bias.

If you’d like a more precise count with specific dates, I’d need to compute each rolling period with exact data, which isn’t fully available here. However, this range aligns with the S&P 500’s resilience over medium-to-long horizons.

Wrap-Up

I’ve heard a few guests on my favorite podcast talking about using AI for research or to re-write their articles to match a certain tone. Interesting…so I thought I would give it a try. Seems like a great way to get some grunt work done and the results seem to align with my own analysis.

But between my analysis and Grok’s, I’m feeling better about my post. I hate to give advice. But I feel better knowing that my decision, which I wrote about in the post is supported by historical data.