Bonds are typically considered a safe asset. Today we’ll talk about the risks and look at some actual examples to demonstrate how, as an investor, we could lose money investing in a bond.

What is a Bond?

Simply put, a bond is a loan to a corporation or government entity. The bond buyer (us) provides the capital (money) and the bond issuer (corporation or government entity) promises to pay a rate of interest throughout the life of the bond and to return the initial investment at matirity.

Let’s take a quick example. Here’s a bond issued by Apple.

There’s a lot here. Read the post on bonds for more detail. Today we’ll stick to some key points.

In this example, Apple needs $2.25 billion dollars to build stuff. So they decide to issue a bond – actually, this is a note not a bond. A note has a shorter duration but otherwise is the same as a bond.

This bond was issued on 2/2/2017 and it matures on 2/9/2027. Apple issued it as a 10 year note and promised to pay holders an annual interest payment of 3.35%. This amount is called the coupon.

Bonds are typically sold at a face value (also known as par value) of $1,000. As an investor, I can but 1 bond for $1,000. I’ll get 3.35% annually with semi-annual payments of 3.35% x $1,000 / 2 = $16.75.

On 2/9/2027, I’ll get my $1,000 back.

Ratings

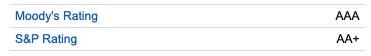

You’ll notice the bond ratings on the left side.

Moody’s and Standard and Poor are independent rating agencies. They analyze Apple’s finances and rate Apple’s ability to make semi-annual interest payments on time and to return the principal.

While I’m sure Apple can find $1,000 to re-pay my bond in 2027, can it come up with $2.25 billion to pay all bond holders? This is what Moody’s and S&P evaluate.

And it appears they think so because AAA and AA+ are top ratings.

Risk v. Reward

Loaning money to Apple is pretty low-risk but i’s not no-risk.

Apple’s annual revenue last year was over $400 billion. They’re doing pretty well. So, paying back $2.25 billion when you’re bringing in $400 billion every year doesn’t seem like a stretch.

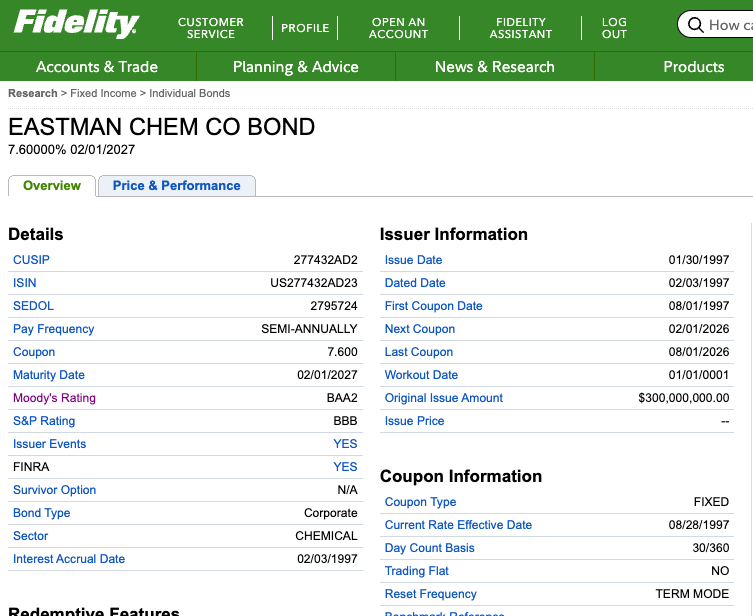

Compare this to a bond from Eastman Chemical

This is a 30 year bond offered by a company with a much lower rating from both Moody’s and S&P. This is higher risk because of both the lower rating and the longer duration.

But for taking on more risk we get a higher coupon. We’ll get 7.6% return per year.

Eastman could miss a payment or 2 or 3. Or it could go bankrupt and stop paying altogether and not return our initial investment.

Saks

I read this today on morning brew.

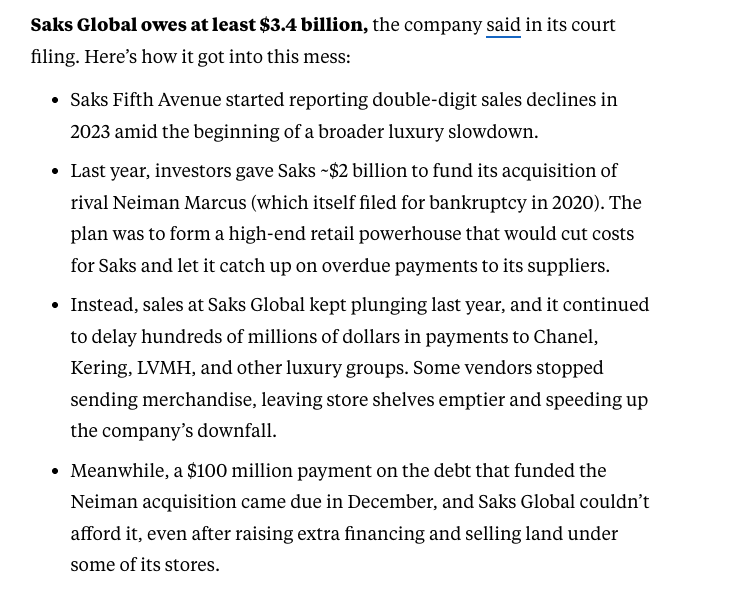

Here’s what that means for investors

Saks was struggling, it bought Neiman hoping to boost sales and cut costs. It had to borrow (from investors by selling bonds) to raise the $2 billion.

It wasn’t able to make its payment of $100 million in December. That means if we had been holding a slice of that bond and we were expecting an interest payment to help pay for some of our Christmas shopping, that payment never came.

This is a real example. A company we know and love can’t make it’s payments. Bond holders lose money.

Saks is re-organizing, not liquidating so this isn’t the end, but we still lost money in December. Maybe we’ll get some of our expected June interest? More to come.

The take-away here is that we can lose money on a bond. Great companies hit rough patches, and when they do, they may find themselves unable to pay their debts. Moody’s and S&P help us evaluate this, but they’re not perfect.

Selling a Bond

We can also lose money selling a bond. Let’s take a quick look.

As an investor, I’m buying that 1st Apple bond above to provide some income and to hopefully provide some reduced volatility compared to equities.

Let’s say I bought a single $1,000 Apple bond in February 2017 when it was issued. I’m getting payments of $16.75 semi-annually.

Then in 2020, I find myself short on cash for my speed-boat payment so I’m forced to sell my bond. As you may remember, 2020 was when inflation started to rear it’s ugly head.

In 2020, Apple and every other company or government entity looking to raise capital, needs to pay a higher rate of interest due to inflation. Apple needs to sell its bonds with a coupon of 5.35% instead of the 3.35% in 2017.

Why Do I Care?

Interesting, but I’m selling, so why do I care?

Here’s why. The face value of our bond is $1,000. That’s what we paid. Try selling that bond that offers 3.35% interest to another investor when they can get a shiny new one that pays 5.35%. Good luck.

We then need to look at total return and reset our expectations for how much we can sell our bond for.

In 2020, I have 7 years left of bond interest payments at 3.35% per year. I’ll get 33.50 per year x 7 years = $234.50 in remaining interest payments.

Investors who are buying the 5.35% Apple bonds today will get 5.35% x $1,000 = $53.50 per year in interest payments. Comparing Apples to Apples (ha ha) between now and 2027, I’ll get 7 years x $53.50 = $374.50 in interest payments.

The new bond gets $140 more in interest between now and 2027. I don’t know about you, but I’d buy the new bond, right?

But bond buyers are capitalists. They only care about total return. So if I compensate bond buyers by lowering my bond price by $140, they’re happy to buy my bond because the total return is the same. So, I set my sell price at $1,000 – $140 = $860.

This is why I care. Interest rates went up. My lower-interest bond is now worth less than new issues. If I need to sell, I’ll lose money.

Mutual Funds

Bonds are complicated so I typically buy bond mutual funds and let an index or a professional choose a basket of bonds. This lowers my risk.

Our 2 examples here show how even that mutual fund can be impacted. When one of the bonds in that mutual fund can’t make payments, my fund interest payment will be lower.

And each bond in that portfolio will be priced daily based on the value of the bond at the current interest rate. This is why bond fund prices fluctuate.

Wrap Up

We can lose money on bonds.

When we shop for bonds, we look at a company like Apple and say, gee that’s a pretty stable company, that bond seems like a no-brainer.

But a lot can happen in 10 years. Look at AOL. It was huge in 2000 and just a few years later it was a distant memory. Same for a lot of companies like General Motors and Lehman Brothers during the 2008 financial crisis.

That said, bonds are an important part of an investment portfolio. They provide income and they offset the volatility of equities.

But we need to remember that we can lose money. There is risk.

Good luck!

And Another Thing…

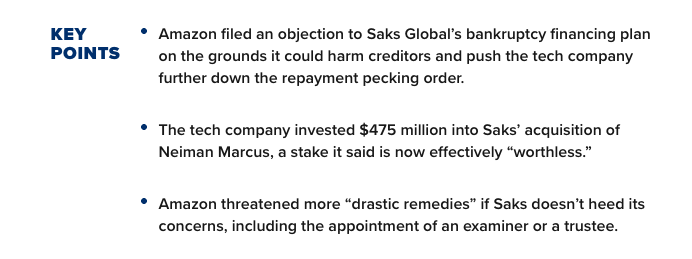

It’s not just the little guy that’s at risk. I saw this just now on CNBC.

Apparently Amazon has some money at risk here.